Inside: This article uncovers the fascinating mysteries behind hummingbird migration including answers to all your burning questions about America’s sweetheart bird such as “How do hummingbirds know when to migrate?” and “How do they know where to migrate to?”. Find out if there’s a specific time to put out and take down your nectar feeder and more things you never thought to ask about hummingbird migration.

Anyone who loves birdwatching as much as I do is bound to be a fan of hummingbirds. These tiny feathered friends are mighty migrators, but not all hummingbirds follow the same course. In this article, I’ll break down some fascinating facts about the various migration patterns of the amazing hummingbird. I hope you enjoy my “who, what, where, when, why, and how” of hummingbird migration.

The Who of Hummingbird Migration

First, let’s look at the unique qualities and migration behavior of specific hummingbird species.

Which Species Migrate?

All hummingbirds are exclusive to the Western Hemisphere, with around 2 dozen species that travel the US and Canada. Hummingbirds are ambitious travelers. For such a tiny bird, their yearly migration journey is an astounding feat.

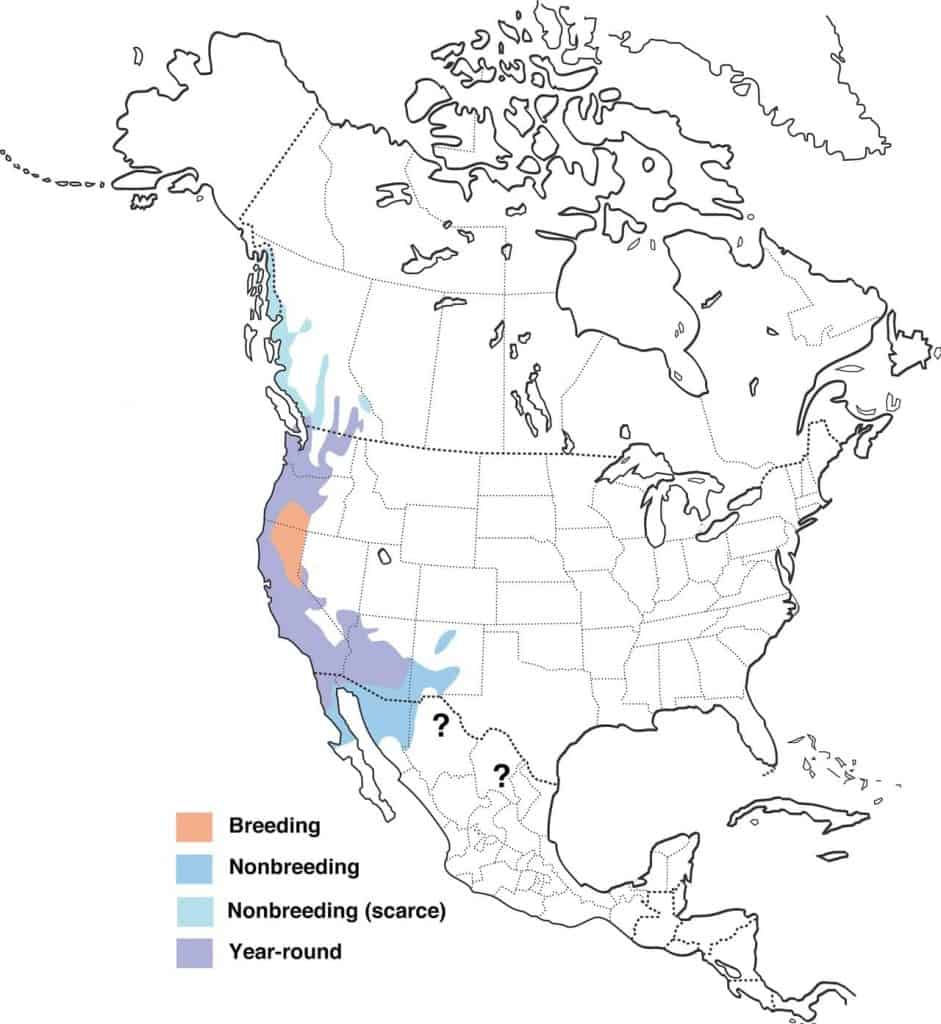

Of the more than 300 different species of hummingbirds, every single one is believed to migrate, except for one. This unique exception is Anna’s Hummingbird. Instead of migrating, they travel within shorter, remote distances to search for food. They remain in their own localized ranges all across the Pacific Coast. This is shown in their range map below.

The following is an alphabetical list of the most commonly known and studied hummingbirds that migrate into the US and Canada:

- Allen’s Hummingbird

- Black-chinned Hummingbird

- Broad-tailed Hummingbird

- Buff-bellied Hummingbird

- Calliope Hummingbird

- Costa’s Hummingbird

- Lucifer Hummingbird

- Magnificent Hummingbird

- Ruby-throated Hummingbird

- Rufous Hummingbird

Unique Migration Behaviors/Patterns for Specific Hummingbird Species

Rufous Hummingbirds make one of the longest migratory trips in the bird world, down to southern Mexico and Central America. Some begin back as early as July traveling south through the Rocky Mountains.

Allen’s Hummingbirds migrate to western Mexico, while other species can be seen traveling south down the Rocky Mountain chain into Mexico and Central America.

Once they’re in the US and Canada, the Ruby-throated Hummingbird travels up to 20 miles in a day, seeking out blooming flowers. The Ruby-throated Hummingbird can travel 500 miles across the Gulf of Mexico in less than 24 hours.

Allen’s Hummingbirds leave their winter stay in early December, arriving along the coasts of California and Oregon for January wildflowers. During the breeding season, male Allen’s Hummingbirds fly towards the coast while the females of the species head further inland where they build their nest.

The Rufous Hummingbird leaves its Mexico where it has been spending winter in early spring, and arrives in Washington State and Canada around May, by flying up the Pacific Coast.

In Central Texas, Ruby-throated and Black-chinned Hummingbirds can be seen in the same areas. Males are usually seen first in Texas, Louisiana, and along the Gulf Coast as early as late January through the middle of March. Ruby-throated can be seen in Florida, Louisiana, and down the lower Texas coast in September. Since they fly independently, they may take a path over the Gulf of Mexico or over land, and sometimes both. Some of them will continue further south and others may stay along the coast from Texas to Florida.

Species that spend their winters in South Louisiana include the Allen’s, the Broad-billed, the Broad-tailed, the Black-chinned, the Buff-bellied, the Calliope, the Ruby-throated, and the Rufous Hummingbirds.

Black-chinned, Calliope, and Rufous Hummingbirds travel north along the western United States on a route they’ve named the floral highway, as they follow the trail of spring flowers into the summer.

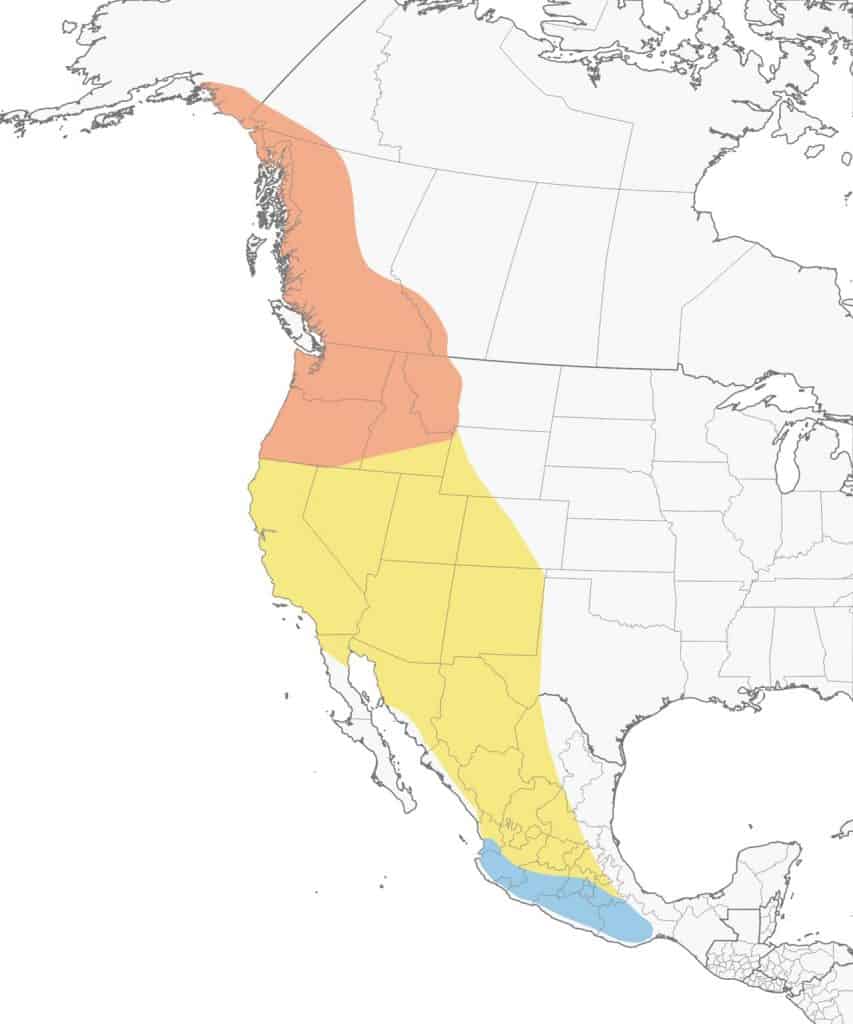

Rufous Hummingbirds win the award for traveling the furthest north of all the hummingbird species. They travel in a clockwise pattern in western North America. They migrate as far as southeastern Alaska. You can see them migrating in southern Mexico in the winter, California in the spring, the Pacific Northwest and Alaska in the summer, and in the Rocky Mountains in the fall. They move up the Pacific Coast in late winter and spring, reaching Washington and British Columbia by May. As early as July they may start south again, traveling down the chain of the Rocky Mountains.

Males vs. Females vs. Juveniles

The male hummingbirds travel ahead of the female and their young, often traveling a separate path from the females, while the juveniles follow the path of their mother. Knowing the order you spot the new arrivals can help you tell which of these three you’re seeing.

You won’t see any juveniles until after the middle of the season, usually around mid-July. They leave their nest in July, and though they are technically adults by that time, you will still see their young plumage.

Finer details are tougher to spot, but using the example of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird, the male has a forked tail while the female and juvenile males have rounded tails with distinctive white tips.

The What of Hummingbird Migration

Next, I want to discuss the substance of their migration and how hummingbirds prepare for their journey.

What Is the Hummingbird Migration?

The hummingbird migration is the travel of individual hummingbirds to the south for the winter months and north for the summer months. Individual migration routes and patterns differ, based on weather, food availability, and species-specific regions.

What Triggers Them to Migrate?

Hummingbirds sense changes in seasonal daylight duration, along with a reduction in the abundance of flowers, nectar, and insects. Their instincts, sharp reasoning skills, and memory let them know it’s time to migrate.

What Do They Do to Prepare for Migration?

Hummingbirds use an enormous amount of energy during migration, flapping their wings as much as 80 times in just one second. That takes a ton of energy, which means loading up on a lot of fuel for the journey. For such tiny birds, hummingbirds have a tough voyage to prepare for, so they know they have to bulk up by as much as 40%, with some species even more.

Check out this hummingbird feeder in Western Texas providing much-needed fuel to several hummingbird species for the migration south across the Gulf of Mexico.

What Is the Hummingbird Migration Route (Patterns)?

Hummingbirds follow numerous migration patterns depending on weather, available food, and environmental factors. There are three main ways to discuss their routes: general, southern, and northern migrations.

General Migration

Some hummingbirds travel towards Texas, others towards North Dakota, while others all the way to central and eastern Canada. Many can be seen in the Great Lakes region on the US and Canadian sides.

After breeding, many adult birds will move toward higher elevations to feast on mountain flowers before heading south in the fall.

Hummingbirds don’t follow a straight path, but rather their migration patterns are determined by where they find the richest food sources along their route. Weather patterns and large weather events will affect exactly when and where they arrive.

Hummingbirds on the east will travel in routes where there’s a very low population because cities and densely populated cities don’t have the flowers they need to make the trip.

Migration South

Hummingbirds follow a different path over interior mountainous regions when they head south, where flowers are blooming early.

Every year, most North American hummingbirds will fly to Central America or Mexico for the winter. They migrate south because they need the right insects and flowers.

It’s believed that the trigger that lets them know the time is coming is the shortening of summer days. Hummingbirds will leave in the late summer to early fall, as early as mid-July, more commonly August or even September, starting with the males heading south as early as July, followed by the females and lastly, the juveniles, which may be as close as a few days behind or linger as long as a few weeks.

The southern migration takes around 2 weeks, with the most treacherous flight across the Gulf of Mexico taking 18-24 hours. Some head south to Mexico and Central America, and some remain in the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts in the US, primarily those that traveled to Canada and have already had a journey of several thousand miles.

They fuel up in the morning, take flight during the day, and seek sustenance again in the late afternoon.

Check out this cool video of an oil rigger’s encounter with hummingbirds on their migration through the Gulf of Mexico.

Migration North

In the west, hummingbirds travel north following the coast where they can find early-blooming flowers.

When the springtime comes, hummingbirds head for the US and Canada to breed. This migration to the north from the tropics is also a result of the heavy competition for food further south, so they return to the US and Canada for the plentiful supply of insects and nectar.

The spring migration from Central America and the southern region of Mexico is a hard task. They face powerful cold fronts, working extra hard against headwinds, fierce rainstorms, almost no shelter, and no food while over open water. The males are always the first to make the journey back north.

By the beginning of March, they can be seen in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. They take an extra month to travel further north. In the Midwest, they likely arrive in April, and most likely in May for Canada.

Many hummingbirds will stay the winter in Central America or Mexico, and migrate north in order to breed in the southwestern states around February but sometimes a little later, and then they will move to regions even further north later in the spring. The further north, the longer the first arrivals are, often not until April and May.

What Is the Longest Hummingbird Migration

The Rufous Hummingbird has the longest journey of all, as far as 3900 miles. Their range map below shows the areas they inhabit including times of migration.

Do Hummingbirds Always Migrate?

Hummingbirds prepare for 2 migrations each year; one for their southern migration, and one time for their return north.

Every species of hummingbird migrates except for Anna’s Hummingbird.

The Where of Hummingbird Migration

Hummingbirds are fascinating to observe, but they’re not always easy to view when migrating. The information below can let you know if you’re fortunate enough to be on one of their many paths.

Where to See Hummingbirds Migrating

You can witness the greatest number of hummingbird species along the Continental Divide because of its clockwise wind rotation, they are utilizing the constant tailwinds.

Costa’s Hummingbirds are small North American desert birds that inhabit the western United States and Mexico but are known to wander eastward and as far north as Alaska and Canada.

Allen’s Hummingbirds travel as far south as southern Mexico in the winter, flying up the Pacific Coast still later in the winter, heading south through the mountains in late summer.

The Black-chinned Hummingbird covers a wide territory, traveling through southern British Columbia, Idaho, Nevada, northern Mexico, California, Arizona, Texas, and sometimes even more states.

Do Hummingbirds Return to the Same Place Every Year?

Many people hope the hummingbirds that visited them last year will return again and wonder if they will.

Hummingbirds return to the same locations year after year – and even the same feeders if they are left out reliably. They can make the two-week journey from southern Mexico to the Great Lakes area, returning to the same feeder they left 7 months before.

The When of Hummingbird Migration

Hummingbirds adjust their migration timing based on changes in weather and food availability. But, their overall goal remains the same. Let’s look at when they will try to make their move.

When & What Months Do Hummingbirds Migrate?

Hummingbirds will begin their southern migration in late summer to early fall, as early as mid-July, more commonly August or even September.

Because their northern migration involves traveling to a wide range of states, some as far as Canada, they can be seen anywhere between March and May throughout their return.

Should Hummingbird Feeders Be Taken Down/Put Up? If So, When?

It’s not necessary to remove feeders, but it’s important to keep them clean. Don’t worry about keeping them filled too long; hummingbirds know when they need to move on. Once there aren’t any signs of visitors it’s okay, but not necessary, to take them down.

The Why of Hummingbird Migration

We’ve learned a lot about where they go and what they do, but why do hummingbirds migrate, to begin with?

Why Do Hummingbirds Migrate?

Hummingbirds are motivated to migrate by the need to escape extreme cold weather. But, if they’re in dangerously cold weather and unable to find enough fuel to sustain the journey, their bodies shut down in a process called “torpor”.Their body temperature drops as much as 50 degrees and their heartbeats slow down to an extremely low pace. When the temperature increases it wakes them up and they continue their migratory flight.

The How of Hummingbird Migration

Everything about hummingbirds is unique. Their methods for migration are no exception.

How Does a Hummingbird Migrate?

Most people may believe that all birds travel together in a flock during migration. Surprisingly, hummingbirds travel alone when they migrate.

Everything in nature always seems to have a purpose, and for birds that travel together in formation, they’re benefiting from the wind draft, flying with efficiency in each other’s path. Hummingbirds are too small to benefit from the same thing, so they’re better off going it alone.

They’re on the constant lookout for flowers to gain the nutrients needed to push forward. For this reason, they fly low so they can spot these food sources.

Hummingbirds rely heavily on their keen eyesight and a strong memory of where they’ve been before. They travel by day, spotting food and flowers in bloom.

The long trek over open waters is a dangerous journey, so they use tailwinds to make their journey as quickly as possible, saving energy any way they can.

How Often Do Hummingbirds Migrate?

Hummingbirds migrate twice every year.

How Far Do Hummingbirds Migrate? In a Day?

While hummingbirds typically travel 22 miles locally in a single day, they’re known to travel as much as 500 miles in the same duration during migration. They won’t stop unless it is a desperate need for food or to prevent death.

Different species of hummingbirds discover different pockets of states to spend more time enjoying birdfeeders and nectar, so some travel much further than others.

How Long Does Hummingbird Migration Take?

Typically, the migration is a two-week journey, but they will adjust to how often they stop along the way, how late in the season they wait to leave or early, depending on weather fronts. They can adjust their travel by a month or so if conditions are more severe, or if they find more food sources along the way.

How Can People Help Migrating Hummingbirds?

Hummingbirds push themselves to their limits during the longest migrations. They return yearly to feeders because they learn where they can get survival food to make the journey. Here are ways you can help migrating hummingbirds:

- Keep your feeders clean and filled with a mixture of 4 parts water, 1 part regular sugar.

- Fill them through early fall, until there are no more signs of late travelers.

- Don’t try to capture a hummingbird if you see one on its own and think it lost its chance to fly with its flock. They will continue on when they know it’s the right time.

- Spreading multiple feeders across the garden can help you get a great view of them traveling back and forth.

- Leaving fresh fruit out will attract fruit flies, which they’ll thank you for.

- Make them feel welcome by planting flowers that provide them with fresh nectar.

- Keep fresh water in a shallow birdbath.

- Don’t use insecticides, so they can fill up on insects.

- Grow shrubs that bloom early.

- Not only can growing a hummingbird-friendly garden bring them back again next year, but it’s also actually helping protect several of their species to thrive.

Conclusion

The hummingbird migration is one of Mother Nature’s amazing creations. These tiny buzzing birds inherently know when to begin their migration, where to go, how they’ll get there, and how to prepare for the trip.

You need not be concerned about when to put up or take down your hummingbird feeders. Like many things in nature, tiny hummingbirds’ survival has very little to do with you and your hummingbird feeder.

Still, if you enjoy watching them up close as I do, don’t overthink it. Put out your feeder in spring when you see them start to arrive. Take down your feeder in the fall when they are no longer around.

Happy birding!